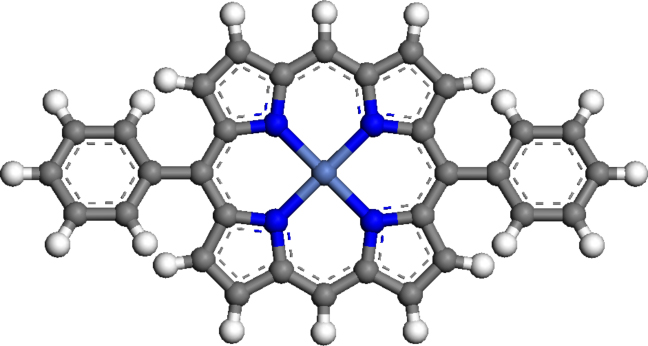

The porphyrin studied in this chapter, (5,15-diphenylporphyrinato)Ni(II), consists of a central Ni-porphyrin macrocycle with two phenyl rings situated at the meso-positions, in the trans orientation, as shown in Figure 4.6.

Porphryins substituted with four phenyl rings have been extensively studied due in part to their relative ease of synthesis, and their self-assembly is well-known [194–198]. The self-assembly and axial ligand lability of a four-fold, meso-aryl substituted porphyrin will be described in detail in the next chapter (Chapter 5); however by investigating the self-assembly of a linear molecule such as NiDPP, interesting phenomena can arise due to its lower symmetry, such as stacking in a preferential direction, and the formation of wire-like structures.

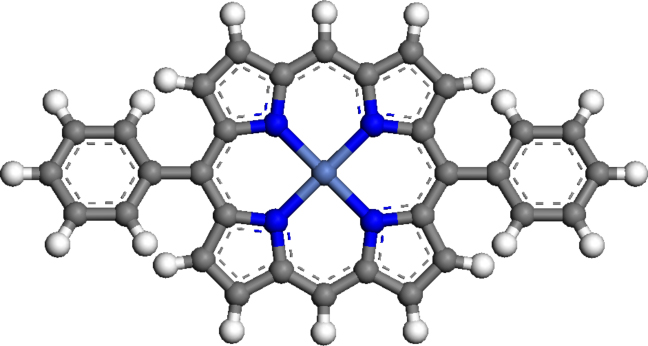

When deposited onto the Ag(111) surface, the NiDPP molecules self-assemble at room temperature into large well-ordered domains. At 1 ML coverage, each porphyrin macrocycle, which includes a central Ni atom, four surrounding pyrrole rings and four C atoms in the meso positions, has a flat orientation on the surface with the macrocycle plane lying parallel to the substrate. Figures 4.7a and 4.7b show typical occupied and unoccupied state STM images taken from the NiDPP monolayer, respectively.

In Figure 4.7a the phenyl substituents are seen as bright oval protrusions, while the porphyrin macrocycle appears dark. In turn, in Figure 4.7b the individual macrocycles appear as bright protrusions, each showing a four-fold symmetry and having dimensions on the order of 1 nm. Such a difference in molecular appearance in Figures 4.7a and 4.7b can be attributed to a difference in the electronic structure between the porphyrin macrocycle and the phenyl substituents and their geometry on the surface.

In Ni porphyrins, the first unoccupied molecular orbitals are localised within the macrocycle and include unoccupied Ni 3d states [199–201]. At a relatively small positive sample bias, electrons tunnel mainly into macrocycle states and not to phenyl rings, making the porphyrin core brighter than its substituents (Figure 4.7b). When tunneling occurs from a number of molecular orbitals localised within both the macrocycle and phenyl rings, the latter appear to be brighter (Figure 4.7a). This is due to the rotated position of the phenyl rings, which makes them topographically higher than the flat porphyrin macrocycle. This simplified view does not take into account the interaction between the molecule and the substrate; however, it is assumed that this interaction is weak for the Ag(111) surface.

It is observed that each Ag(111) terrace is covered with a single molecular domain with terrace widths of up to 100 nm. The NiDPP overlayer has an oblique close-packed structure and consists of alternating molecular rows. The molecules along each row are aligned parallel to each other, while the molecules in adjacent rows are rotated by approximately 17° with respect to each other. This leads to the tilted-row pattern seen in Figure 4.7b, arising from pairs of phenyl rings aligned with one another.

The proposed model of the NiDPP monolayer on the Ag(111) surface is shown in Figure 4.7c. The unit cell of the NiDPP lattice has the following parameters: a = 2.00 ± 0.05 nm, b = 1.60 ± 0.05 nm, γ = 85.0 ± 0.5°. The formation of ordered structures of this extent indicates a low diffusion barrier for the molecules on this surface at room temperature. Furthermore, a relatively weak (van der Waals) intermolecular interaction, involving the hydrogen atoms and phenyl rings of neighbouring NiDPP molecules dominates over a weaker bonding between the molecules and the Ag(111) substrate. It is noted that the molecules desorb from the surface at a temperature of approximately 430 K, which provides further evidence for a physisorbed system weakly bonded to the substrate.

As seen in Figure 4.8, the NiDPP molecular rows are oriented along the substrate step edges. The steps follow one of the close-packed directions of Ag(111), denoted here as [10], as derived from STM and LEED measured from the clean substrate. This indicates that the overlayer growth starts from the Ag(111) step edges, which imparts a direction to the resulting molecular structure. This is a clear indication that, despite a weak molecule–substrate interaction, Ag(111) plays a crucial role in the adsorption and arrangement of the molecules.

A similar type of growth has been found for other molecular layers on surfaces with a relatively low reactivity [46, 202, 203]. As shown in the overlayer model in Figure 4.7c, the porphyrins and the substrate form an almost perfect 2:9 coincidence structure along the [10] direction of the Ag(111) surface, where every second molecule along this direction coincides with every ninth silver atom. This direction coincides with the long diagonal of the NiDPP overlayer unit cell.

All STM images of NiDPP on the Ag(111) surface show the close-packed structure of the self-assembled layer with a relatively small separation between the molecules. This is a result of significant rotation of the phenyl rings, imaged as oval protrusions (Figures 4.7a and 4.8a). The plane of the phenyl rings is usually rotated by approximately 60° with respect to the macrocycle plane according to ab initio calculations, STM and X-ray absorption experiments [11, 192, 204, 205]. Such rotation allows the NiDPP molecules to approach each other on the surface in a specific manner and form an extended close-packed structure to minimize the surface energy.

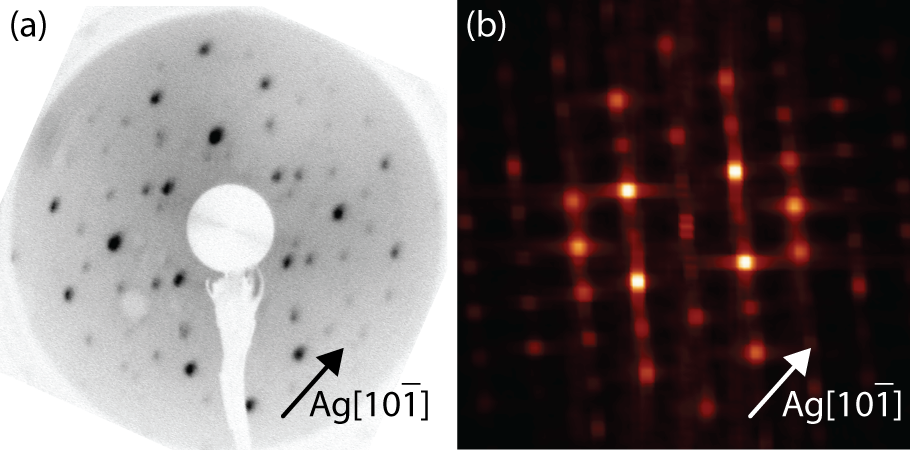

Figure 4.9a shows a LEED pattern obtained from 1 ML of NiDPP deposited on the Ag(111) surface. This LEED pattern with an oblique unit cell exhibits good agreement with the two-dimensional fast Fourier transform (2D-FFT) (Figure 4.9b) of the STM images. Note that although similar in concept, LEED and FFT will not agree perfectly, since LEED averages over a much larger area (∼ µm) than the STM image from which the FFT is calculated (∼ 10nm), and that LEED can include contributions from the substrate and multiple scatterings. Nevertheless, this implies that the surface is covered by a single domain and that the STM images included are representative of the overlayer structure.

The silver-passivated Si(111) surface has a  ×

× R30° reconstruction

and consists of the honeycomb-chain trimer structure, as explained in

Section 4.3 [187, 188]. The reactivity of this surface lies between that of the

Ag(111) and the clean Si(111). It is expected that the NiDPP interaction

with the Ag/Si(111)-

R30° reconstruction

and consists of the honeycomb-chain trimer structure, as explained in

Section 4.3 [187, 188]. The reactivity of this surface lies between that of the

Ag(111) and the clean Si(111). It is expected that the NiDPP interaction

with the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° surface will be stronger than that of

Ag(111).

R30° surface will be stronger than that of

Ag(111).

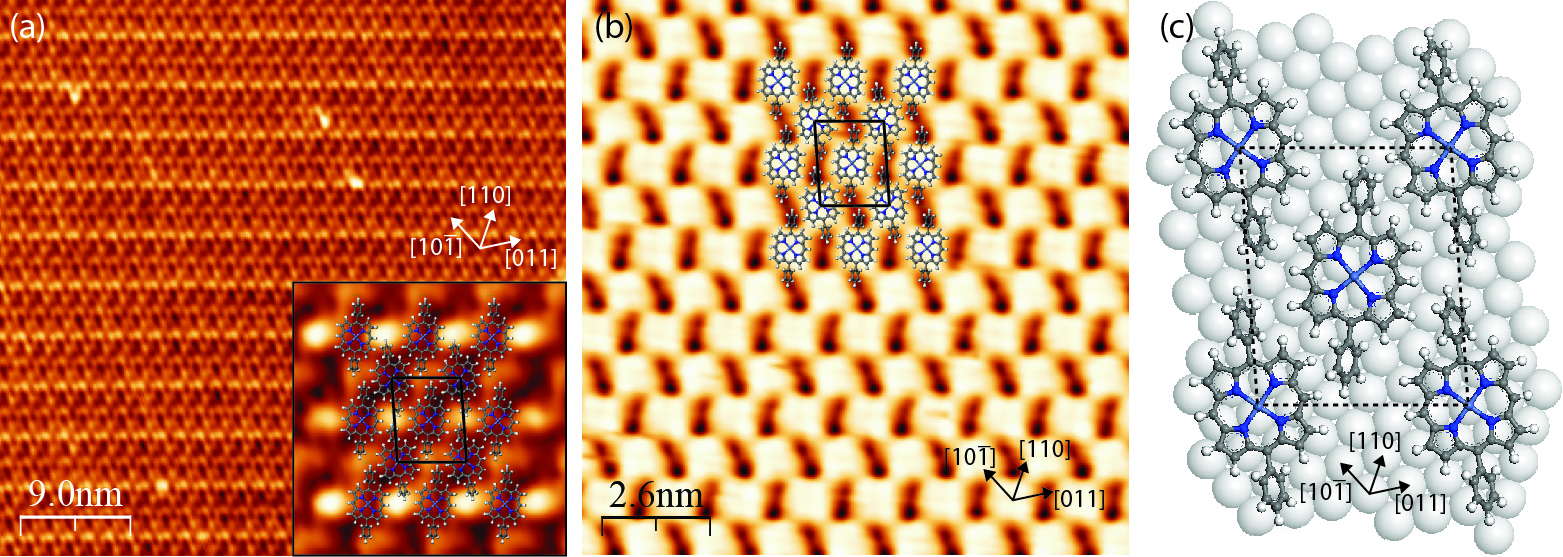

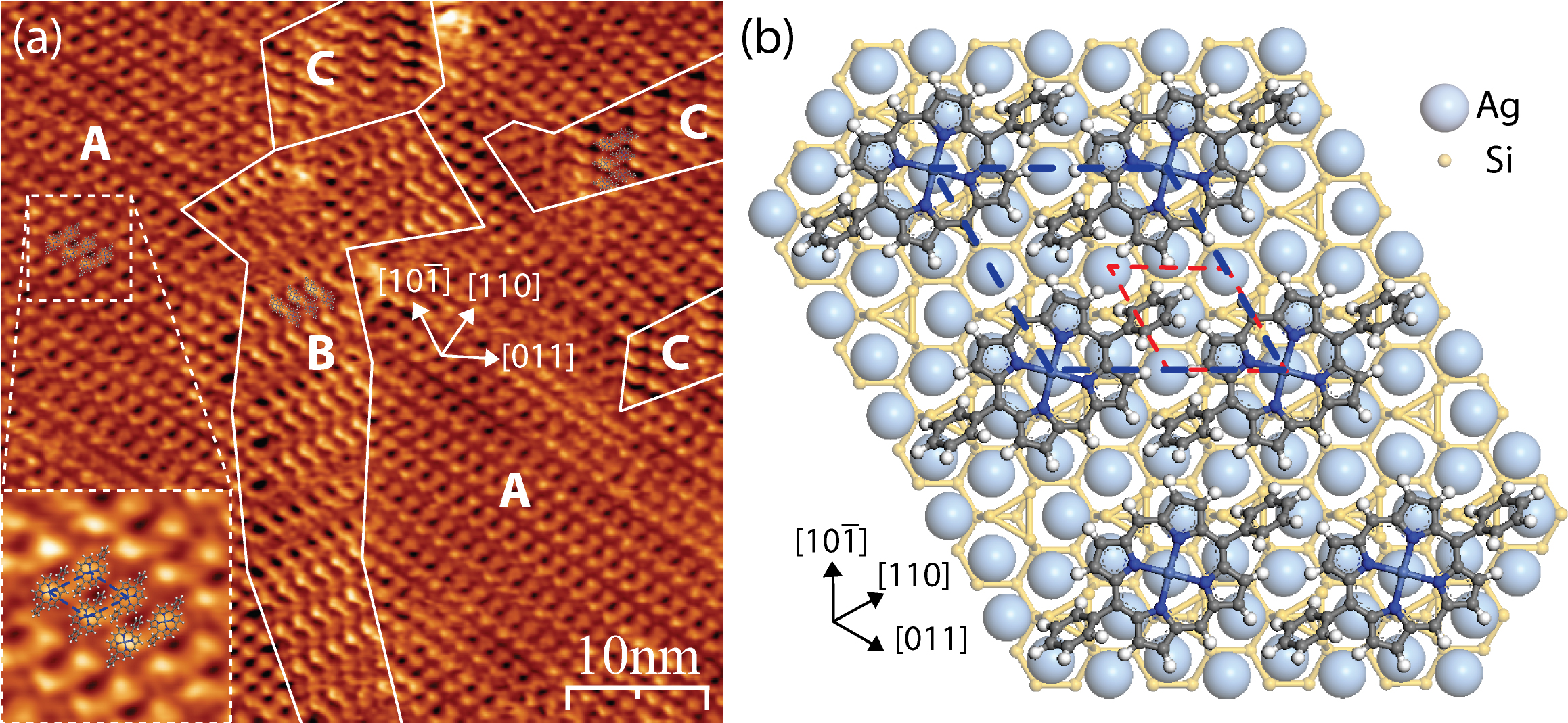

Figure 4.10a shows a typical STM image of a monolayer of NiDPP molecules

deposited on the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° surface. The NiDPP molecules form a

close-packed structure of dimer rows on this surface. There are three domains,

labelled A, B and C, observed on the same terrace in Figure 4.10a. All domains

have a similar pseudo-hexagonal structure and are rotated by 120° relative to each

other following the three-fold symmetry of the underlying substrate. The inset in

Figure 4.10a shows in detail the close-packed structure of one domain

(A).

R30° surface. The NiDPP molecules form a

close-packed structure of dimer rows on this surface. There are three domains,

labelled A, B and C, observed on the same terrace in Figure 4.10a. All domains

have a similar pseudo-hexagonal structure and are rotated by 120° relative to each

other following the three-fold symmetry of the underlying substrate. The inset in

Figure 4.10a shows in detail the close-packed structure of one domain

(A).

×

×  R30° surface: It = 0.8 nA, Vsample = 1.35 V,

50 nm × 50 nm. Three domains of dimer rows rotated by 120° to each other

are present and are labelled A, B and C in the image. The inset shows the

detailed structure of the domain A. (b) Schematic representation of one

domain of the NiDPP overlayer on the Ag/Si(111)-

R30° surface: It = 0.8 nA, Vsample = 1.35 V,

50 nm × 50 nm. Three domains of dimer rows rotated by 120° to each other

are present and are labelled A, B and C in the image. The inset shows the

detailed structure of the domain A. (b) Schematic representation of one

domain of the NiDPP overlayer on the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° surface.

(a) has been smoothed using a 3 × 3 matrix to remove mechanical noise.

R30° surface.

(a) has been smoothed using a 3 × 3 matrix to remove mechanical noise.

The existence of three different domain orientations on the same terrace of the

Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30°, in contrast with single-domain terraces for Ag(111),

implies a much stronger molecule–surface interaction, as expected for the

more-reactive Ag-passivated Si(111) surface. When deposited at room

temperature, the movement of the molecules on the surface is restricted, with

preferential binding sites dictated by the pseudo-hexagonal structure of the

underlying surface.

R30°, in contrast with single-domain terraces for Ag(111),

implies a much stronger molecule–surface interaction, as expected for the

more-reactive Ag-passivated Si(111) surface. When deposited at room

temperature, the movement of the molecules on the surface is restricted, with

preferential binding sites dictated by the pseudo-hexagonal structure of the

underlying surface.

This results in an oblique (pseudo-hexagonal) unit cell with lattice parameters

of 1.4 ± 0.1 nm × 1.3 ± 0.1 nm at an angle of 60 ± 2°. The proposed model of the

NiDPP monolayer on the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° surface is shown in

Figure 4.10b. It is noted that twice the distance between the Si trimers is equal to

1.33 nm. In order to minimize the number of non-equivalent adsorption sites and

the lattice mismatch, the NiDPP monolayer is stressed on this surface. This

results in a slightly denser overlayer structure compared to the one observed on

the less-reactive Ag(111) surface. The packing densities of the NiDPP overlayer

on the Ag/Si(111)-

R30° surface is shown in

Figure 4.10b. It is noted that twice the distance between the Si trimers is equal to

1.33 nm. In order to minimize the number of non-equivalent adsorption sites and

the lattice mismatch, the NiDPP monolayer is stressed on this surface. This

results in a slightly denser overlayer structure compared to the one observed on

the less-reactive Ag(111) surface. The packing densities of the NiDPP overlayer

on the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° and the Ag(111) surfaces, calculated

from the proposed models, are equal to 0.67 and 0.63 molecules per nm2,

respectively.

R30° and the Ag(111) surfaces, calculated

from the proposed models, are equal to 0.67 and 0.63 molecules per nm2,

respectively.

×

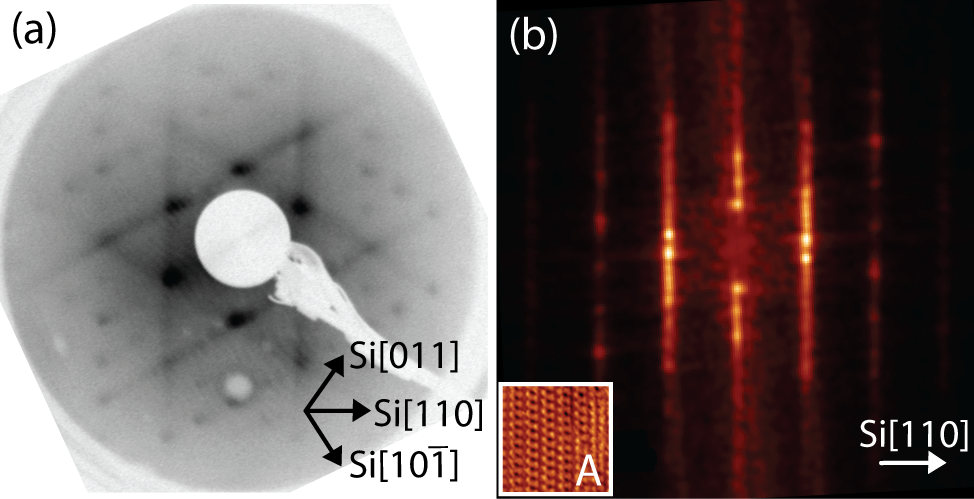

× R30° surface acquired at a kinetic energy of 25 eV. (b)

Two-dimensional fast Fourier transform calculated from the STM image of

one domain (A) shown in Figure 4.10a, indicated by the inset. The primary

substrate directions are indicated by arrows, with only that of the A domain

shown in (b).

R30° surface acquired at a kinetic energy of 25 eV. (b)

Two-dimensional fast Fourier transform calculated from the STM image of

one domain (A) shown in Figure 4.10a, indicated by the inset. The primary

substrate directions are indicated by arrows, with only that of the A domain

shown in (b).

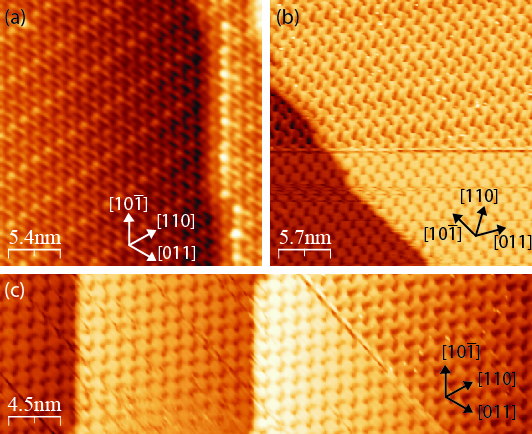

Figure 4.11a shows a LEED pattern obtained from approximately 1 ML

of NiDPP deposited on the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° surface. It has a

pseudo-hexagonal structure confirming the presence of three domains of

the molecular overlayer. By comparing the 2D-FFT calculated from the

STM image of a single domain A (Figure 4.11b) with the experimental

LEED pattern, it is clear that the dominant features arise from the three

equivalent domains observed in Figure 4.10a, oriented at 120° to one

another.

R30° surface. It has a

pseudo-hexagonal structure confirming the presence of three domains of

the molecular overlayer. By comparing the 2D-FFT calculated from the

STM image of a single domain A (Figure 4.11b) with the experimental

LEED pattern, it is clear that the dominant features arise from the three

equivalent domains observed in Figure 4.10a, oriented at 120° to one

another.

It is also evident from the symmetry that each orientation contributes equally

to the LEED pattern, indicating that no one orientation is preferred over the

others. This is in agreement with the STM data showing that the NiDPP

overlayer structure consists of dimer rows growing in three equivalent directions,

dictated by the hexagonal symmetry of the Ag/Si(111)- ×

× R30° surface.

The significant streaking of the LEED spots (Figure 4.11a), which are also visible

in the 2D-FFT (Figure 4.11b), is a result of the dimer row structure observed in

STM images. This streaking indicates the presence of disorder along the molecular

rows and arises due to a variation in the lattice parameter of the molecular unit

cell in the direction parallel to the molecular rows. This in turn is attributed to

non-equivalent rotation and/or bending of the individual phenyl rings in order to

minimize the lattice mismatch between the NiDPP overlayer and the

substrate.

R30° surface.

The significant streaking of the LEED spots (Figure 4.11a), which are also visible

in the 2D-FFT (Figure 4.11b), is a result of the dimer row structure observed in

STM images. This streaking indicates the presence of disorder along the molecular

rows and arises due to a variation in the lattice parameter of the molecular unit

cell in the direction parallel to the molecular rows. This in turn is attributed to

non-equivalent rotation and/or bending of the individual phenyl rings in order to

minimize the lattice mismatch between the NiDPP overlayer and the

substrate.